I first met Richard Toensing at the 2004 Sacred Music Institute of the Antiochian Archdiocese in Ligonier, Pennsylvania. I doubt he remembered the meeting, but I certainly remembered him, and when Cappella Romana premiered and recorded his Kontakion on the Nativity of Christ, I remember thinking, Wow — here is one of our current great American composers turning his talents to Orthodox sacred music.

I first met Richard Toensing at the 2004 Sacred Music Institute of the Antiochian Archdiocese in Ligonier, Pennsylvania. I doubt he remembered the meeting, but I certainly remembered him, and when Cappella Romana premiered and recorded his Kontakion on the Nativity of Christ, I remember thinking, Wow — here is one of our current great American composers turning his talents to Orthodox sacred music.

When I say one of the greats, I mean it. Born in St. Paul in 1940, Richard made conducting and composing the cornerstones of his musical life. A good Minnesota Lutheran early in life, he first went to St. Olaf College, and then studied composition at University of Michigan. Most of his career he spent as part of the composition faculty of University of Colorado at Boulder, where he served at various points as head of the Electronic Music Studio, and the director of the New Music Ensemble. As a teacher, he trained dozens upon dozens of the next generation of composers, and was a beloved mentor to many. As a composer, if there could be a person more ensconced and recognized in the world of twentieth century art music, I don’t know who it could be; his music was performed on four continents, and he won several awards for his music, including the Guggenheim Fellowship.

At the same time, Richard was also always a dedicated church musician, first in Lutheran communities, and then after his conversion to Eastern Orthodox Christianity, at St. Luke’s Antiochian Orthodox Church in Erie, Colorado. He served the Department of Sacred Music of the Antiochian Archdiocese of North America for years, and was a fixture of the annual Sacred Music Institute, where I first met him. He composed many wonderful pieces of liturgical and para-liturgical choral music for the Antiochian Archdiocese, and his concert works were also greatly informed by his faith, including the Kontakion, a setting of St. Romanos the Melodist’s lengthy Christmas hymn. His music can be thought of as a synthesis of everything he encountered in the world of Orthodox music; you hear a little bit of everything from Byzantine chant to Russian harmonies, and it is informed by his own sensibilities as a formally-trained composer for the concert hall in the twentieth century.

Richard was never anything short of incredibly kind and generous to me; I first contacted him to participate in a symposium on Orthodox music I was organizing at Indiana University, and he happily agreed to come. It also turned out that one of my oldest friends in the world, Matthew Arndt, whom I’ve known since the seventh grade, was now a music theory professor at University of Iowa and who was directing the choir at St. Raphael of Brooklyn Antiochian Orthodox Church in Iowa City, and he had been Richard’s student at UC Boulder for his Masters degree. We all had a fantastic time singing Tom Lehrer songs together around the dinner table when the symposium was over, and the twinkle in Richard’s eye for “Poisoning Pigeons in the Park” made it an evening I’ll never forget. When the board members and I were helping to found the Saint John of Damascus Society, he was wonderfully supportive and full of excellent suggestions, and graciously accepted our invitation to serve on the Advisory Board.

Richard had a great deal of positive, constructive influence on how the Psalm 103 Project was organized. Beyond simply being a composer for hire, his reach as a teacher was evident in Matthew’s contributions, and as a colleague, he made excellent suggestions during the planning sessions that helped us all to see what the final shape of the score might be. Richard asked some of the hardest questions when we first proposed the idea, and at times he seemed the most dubious about the prospect, but he was also the first person to come to me at the end of our working weekend to say, “You know, this is going to work, and it’s going to be really good.”

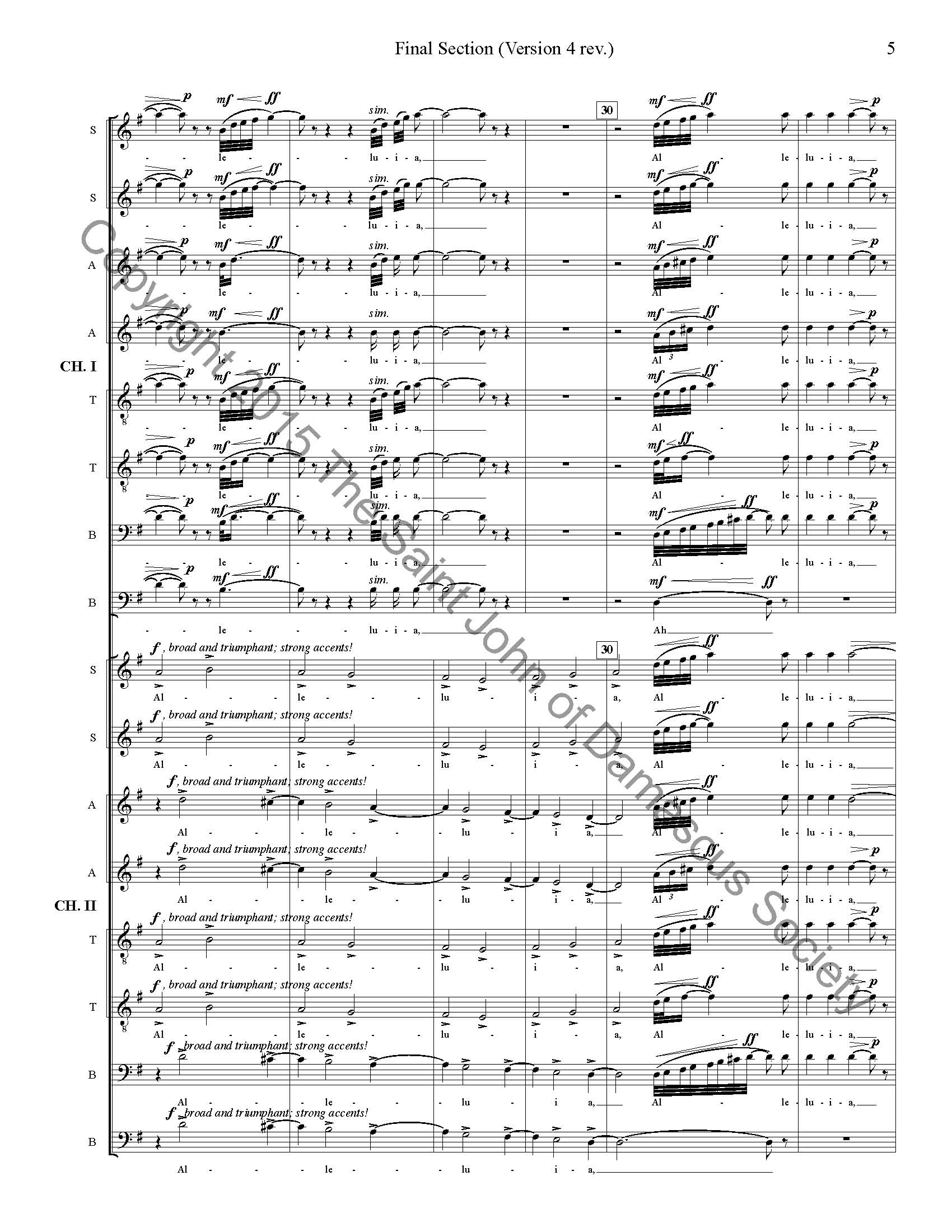

Richard was also the very first of the six composers to finish his section of the score, sending me finished music at the beginning of February 2014. I can tell you that what he contributed to this effort as a composer is a masterwork all by itself. We told all of the composers to write for the best choir they could think of; “Write for a Ferrari,” we said. “Swing for the fences.” Well, everybody did that, but I knew Richard was trying to figure out just how far he could go when I got an e-mail from him asking, “Can I write something for a countertenor?” When I opened his finished score, I saw music for antiphonal 8-voice choirs. When I listened to the MIDI file and followed along with the score, my jaw dropped. He had given us a truly amazing gift.

In the last conversations I had with him at the beginning of that summer, he told me that he was excited about how everything was taking shape, and that he had a lot of confidence in how it was going to go.

Since Richard’s passing, he has never been far from our hearts and minds. In October 2014, one of our board members got married; before his repose Richard had composed a lovely setting of “Draw Near, O Bride of Lebanon” for her as a wedding gift, and the group of us singing for her wedding were honored to sing it for the first time during her procession into the nave. At this year’s Sacred Music Institute, the SMI Chamber Choir sang two pieces of his, “Of thy Mystical Supper” and “Your Bridal Chamber I See Adorned”, the latter of those submitted to the Department just two days before he passed. I’ll just note as a technical point that the piece is scored for women’s voices in C minor, and the overall effect is one of harmonies suspended in the air — and at the very end, for his last chord, rather than a C minor triad, he ends on an open fifth, G and D, implying a dominant fifth except with no third. It sounds incomplete, like the piece isn’t over.

As Richard’s friend, I very much believe that’s true.

The Psalm 103 Project is a collaborative effort, six artists brought together — not so that each one can describe a different part of the elephant, so to speak, but so that they can put their different parts together and reveal something about the entire elephant. Within that collaborative framework, we were all honored to work with a musical servant of the Orthodox Christian Church in North America, a peerless composer of English-language sacred music, and an outstanding artist. Without Richard’s influence as a teacher, a colleague, and a fellow Orthodox Christian, it could have never come together the way that it has. It is our job now to make sure that the widest possible audience will get to hear the gift that Richard and his co-composers have given the Orthodox world, and to recognize the God-given artistry that he and the others put to work in the service of Christ and His Church. Richard’s works will surely have a life in our concert halls and churches far beyond any of us, and with your help, the premiere performances and the CD release of The Psalm 103 Project will be a musical memorial to Richard that will honor his legacy in the manner that he deserves.

Memory eternal, my friend.

Boston, MA – 12 August 2015

Special thanks to Janet Braccio, Richard Toensing’s longtime publicist, for the photograph of Richard that opens this post.